12 Interesting Items at the Pocahontas County Historical Society Museum

The Pocahontas County Historical Society Museum is a beautiful, small building located in Laurens, Iowa. The building was funded by Andrew Carnegie in the early 1900s. Andrew Carnegie was one of the robber barons. He made a lot of money in the 1800s selling steel to the railroads, and he gave a lot of that money away. One way he did this was by funding libraries throughout the country. Many of the libraries he funded are unbelievably ornate, but not the one in Laurens. One of the volunteers who runs the museum calls the building “Carnegie-lite” as it is much more modestly designed. Laurens was the smallest town in the nation to get a Carnegie library in 1910. Want to know a fun fact? All of the Carnegie libraries were required to have stairs leading into the building to show that you were taking steps into enlightenment and raising yourself up. It became a museum in 1977 and is now on the National Registry of Historic Places.

There are plenty of one-of-a-kind objects to be found in the museum. The items were donated by local families whom the museum relies on to continue growing. They are very grateful for all the people who have contributed to it throughout the years.

Now, here are a dozen of the most interesting contributions that you need to see for yourself.

The Rope Bed

Rope beds were popular from the 16th century to the 19th century. Rope beds were usually four poster beds, just like the one in the Pocahontas County Historical Society Museum. Ropes were laced across the bed frame to support the mattress. These ropes need to be tightened quite often in order to ensure firm support and a good night’s sleep. Hence, the phrase “sleep tight” which originated due to the rope bed.

The rope bed featured at the museum is more than just a reminder of how grateful you should be for that memory foam mattress and box spring you have now. It is also the very bed where the first child of European settlers, who were members of the Lizard Creek settlement, was born in Pocahontas County. His name was Charles J. Kelley and his mom gave birth to him on May 6, 1848 on that very bed.

Wiegert-Kalsow Wedding Dress

Clothing in the late 19th century was nothing like the clothing we have now. In the early part of the 1890s, women wore tight bodies with high collars and narrow sleeves, and skirts were a simple A-line. Wedding dresses followed this pattern, and were often different colors. Normal families could not afford white fabric, and, even if they could, it wouldn’t be practical as dresses had to be worn more than once due to financial restraints and availability of fabric and seamstresses. All of this can be seen in the wedding dress on display at the museum.

The wedding dress belonged to Martha Kalsow who married Fredrick Wiegert Jr. in 1897. The Wiegert family owned and farmed the Wiegert Farmstead near Palmer, Iowa for over 100 years. The family and their land has a long history in Pocahontas County. Harry Wiegert, son of Martha and Frederick, was the third generation in his family to call this place home. The 120 year old house still has no electricity or indoor plumbing, and is only one of very few places in the state that is like that. A windmill stands ready to pump water for livestock, and, until his death in 1980, Harry drew water from that pump by hand. He also heated the house with wood from local trees, and used kerosene lanterns for light. He lived the way he grew up, thereby leaving an historical and natural treasure for many to enjoy. Henry donated part of the land to the county’s conservation commission. There is a festival held there every year called Wiegert Fall Fest that honors the old ways of farming and living that the family were known for.

Des Moines Township School Picture

Back in the early 1900s, the Des Moines Township, which is where Rolfe now sits, was the first school district to consolidate their country schools. At the time of the consolidation, there were six schools on the west side of the Des Moines River. However, not everyone was on board with the plan; most people felt the high school should be in the town of Rolfe and some wanted the schools to stay right where they were. To avoid a confrontation with the townspeople, the schools were moved in the dead of night. They lined up the six schools in a row with a board walk along the front of them, and they used these six buildings as the schoolhouse while the new consolidated school was being built. The first year of classes began in 1916.

Early Football Uniform

When watching football, it’s easy to take for granted the equipment utilized by participants and assume it is the same as it has always been. But rules and regulations at the start of football were very different than they are now. In fact, it was more similar to rugby than anything else. And, just like the game, the uniform has changed drastically in the sports 144-year history as you can see with this football uniform from 1916 that is set up at the Pocahontas County Museum.

Uniforms were nearly non-existent in the early days. There were no helmets in the beginning, and the first helmets, made in the early 1900s, barely did more than cushion the blows; they were usually leather with large metal face masks, but they did more to cover the face than the actual head. Should pads actually came before the headgear, having been invents in the late 1800s. They were made out of leather, wool, and canvas, and was more useful in easing the players mind than actually protecting him. Finally, we have the hip pads which was basically padded canvas. Apparently, the uniform was also confusing. Dorothy, one of the tour guides at the museum, told me that the hip pads were displayed backwards for years. “We thought that there should be more protection in the front,” she explains through her laughter. “Eventually, someone told us that it was meant to protect the kidneys.” The fact 23 people died playing football in 1905 shows just how useless these early forms of “protection” really were.

Japanese Balloon Bombs

During WWII, the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Army fought several long and bloody battles in the Pacific in an effort to fight Japan which had bombed Pearl Harbor. On April 18, 1942, the United States planned a surprise attack on Tokyo’s manufacturing centers to delay production of weapons and cause panic. Though there was actually little damage, it was enough to boost American morale. However, the wound it delivered to Japan’s pride led Japanese leaders to pursue more offensive plans. They decided to return the favor and bomb the United States; however, Japan’s manned aircrafts were incapable of reaching the West Coast. This would not deter the Japanese; they decided to use a jet stream located 30,000 feet above Japan to transport hydrogen filled balloons to the United States. For two years, the military would produce thousands of these balloons then attach incendiary devices and high-explosive bombs to the balloons via a 40-foot rope. The balloons were meant to drop over North America and spark massive forest fires on the West Coast to divert resources from the war effort. More than 9000 balloons were launched between 1944-1945 in an operation codenamed “Fu-Go.” Most balloons fell into the Pacific Ocean, with only 300 reaching the US and Canada and only one resulted in any injury. However, they didn’t stop at the West Coast. Some made it as far as Iowa, and two even landed in Pocahontas County. The one of them was almost completely intact and is currently at the Gold Star Museum in Johnston. Pieces of the other one, which landed right outside of Laurens, were ripped off and taken as souvenirs by local townsfolk. Those pieces can be found in the Pocahontas County Historical Society Museum.

Antique Farming Tools

Pocahontas County was settled much later than most of Iowa, around the mid-1800s, because the land was so much wetter than surrounding areas. It was basically a marsh. The only viable farmland was on the top of hills; it wasn’t until they drained the land that it became farmable. This was done by placing tiles throughout the county allowing all the water to drown out into the rivers. At first, they had to use wooden plows to dig the ditches, but they would just fill in too fast. Eventually, they would use steam shovels to dig the bigger ditches, but the rest of the digging happened by hand. They would use a special spade to dig out the clay-like parts of the Earth before being able to place the tiles. It was a lot of back-breaking work that had to be done to make the county livable. The farm tools they would have used to do this work are on display in the basement of the Pocahontas County Museum.

Hay Twist

Because there are so few trees in Pocahontas County, pioneers who settled here had to find alternatives for fuel to cook and heat their homes. The best method they found was to use prairie hay. To avoid excessive smoke and to make the hay burn longer, the settlers made the hay more compact by twist it into skeins called hay twists – an example of which is in the basement at the museum.

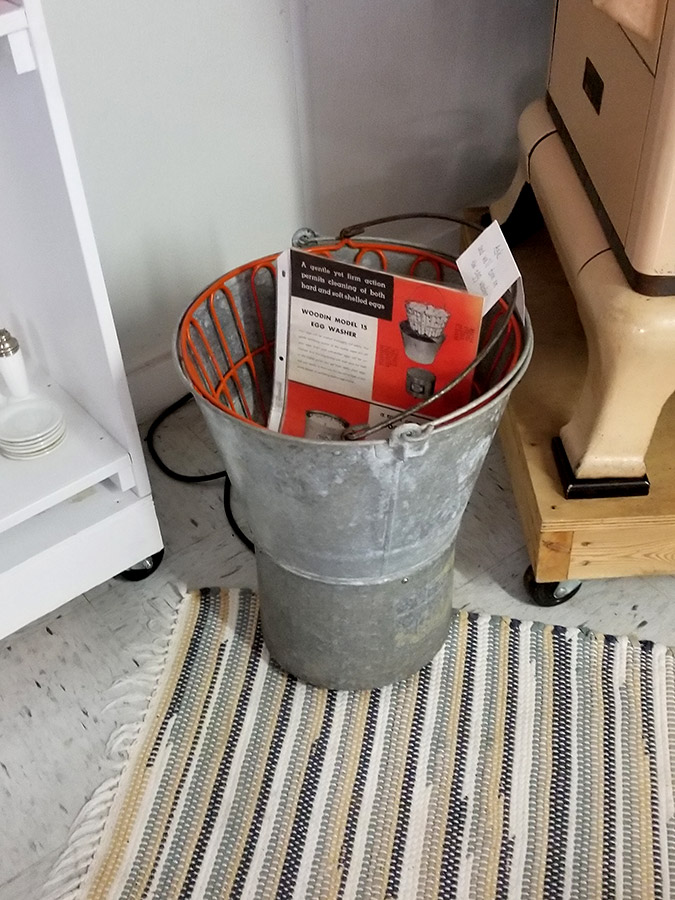

Egg Washer

The egg washer, also in the basement at the museum, was invented by a man from Ware. Walter Woodin’s story on why he created the egg washer is quite interesting. Back in the day, women would take care of the chickens and their eggs. One day in 1956, Walter had to take care of them because his wife fell ill. Well, he thought that all the work it took to wash the eggs was ridiculous so he came up with the idea for an egg washer. It was very clever and simple. You just fill the bucket full of eggs and add water. When you plug it in, it gently moves back and forth to clean the eggs. You can even see it in action at the museum; just ask a volunteer to plug it in! There was a factory in Laurens that manufactured the egg washer and they sold over 25,000 of them in the first two years. The Woodin Egg Washer, as it came to be known, was the first oscillating electric egg washer on the market.

Surveyor’s Instrument

The first surveyors who came to Pocahontas County declared a great part of the county “second rate, full of irreclaimable marshes.” When the first settlers arrived, they planted grain on the higher ground and left the wet areas for pasture. The farmers wanted to farm more land, and ultimately, they dug ditches. The county was drained leaving some of the richest soil in the world. Mr. Malcolm, one of the early surveyors in the county, looked through this surveyor’s instrument as he did his work.

100-Year-Old Jar of Cherries

One of the more peculiar items at the museum is a jar of cherries that was canned almost 100 years ago. Winnie Rigby canned these cherries in 1920 during one of her first years of marriage. Instead of using them, she kept them as a memento of her marriage for her whole life. When she moved to Laurens, she brought the jar with her. When Winnie died, her daughter knew she couldn’t just throw this jar away. Instead, she gave it to the museum so her mother’s memory would live on.

Cook Stove

Before electricity came to the farm, a cook stove like this was the heart of the home. Besides cooking and baking, the stove doubled as a way to heat the house. A water reservoir provided the hot water for baths and washing dishes. This well-loved cook stove, fueled by corn cobs, spent its life in the Wallin farmhouse. Lyle Wallin remembers taking out the thick book filled with recipes and making corn bread whenever his mom put a roast in the oven.

Civil War Prayer Book

David Nowlan, a native of Illinois, enlisted in the Union Army in 1861 at the age of nineteen. He carried this tiny prayer book in the pocket of his uniform as he fought in multiple battles. After the war, he studied medicine. Eventually, he settled in Havelock and became one of the county’s earliest doctors. When he died, his sister, who belonged to the Holy Cross Order of nuns, kept the prayer book safe. Eventually, relatives donated this precious item to the museum.